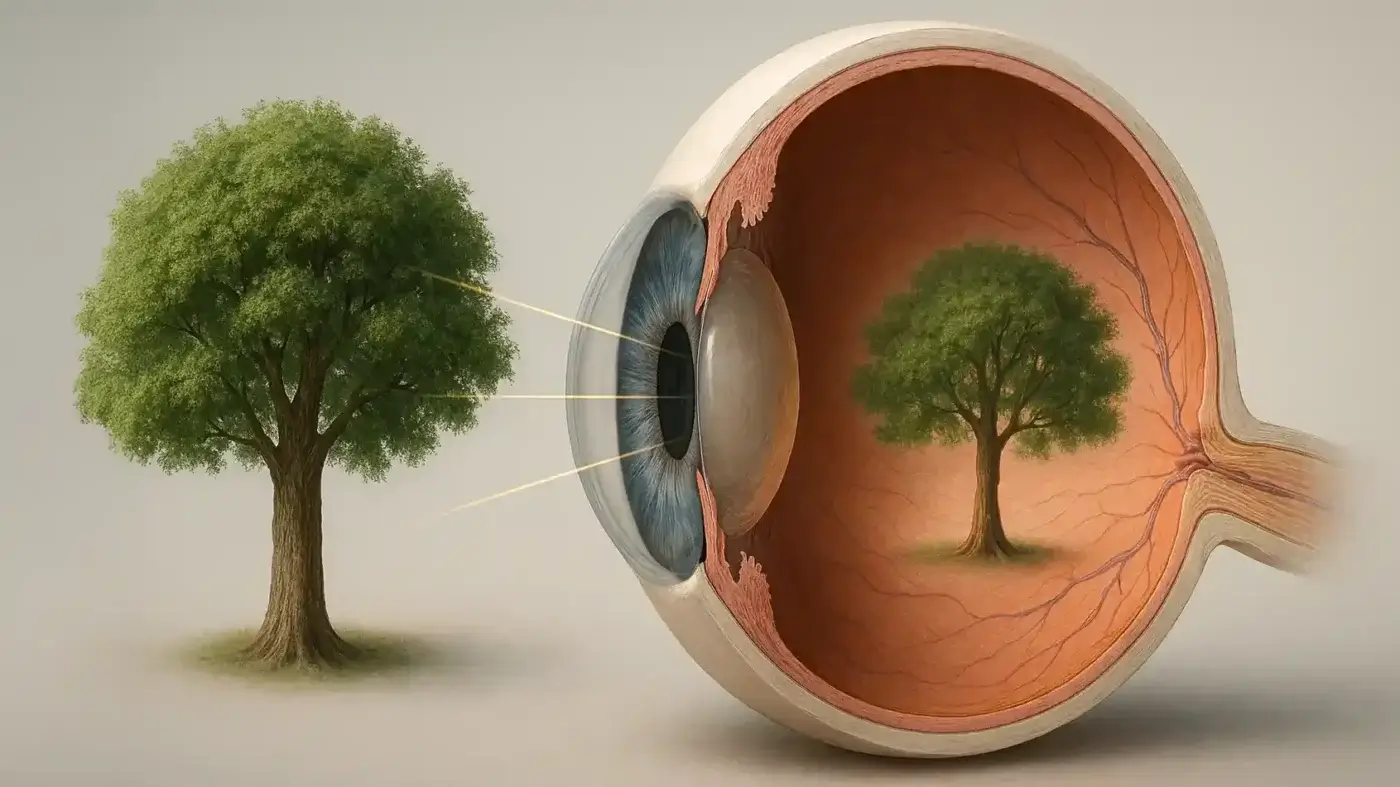

Camera Obscura and the Human Eye

Leonardo da Vinci was among the first to recognize the striking resemblance between the Camera Obscura and the human eye. Both rely on the same optical principle: light enters through a small opening into a dark chamber and forms an image on the opposite surface. At first glance, the two systems seem almost identical, yet the differences are what reveal the deeper mechanics of human vision.

The human eye

In the eye, the eyeball acts as the chamber, the pupil regulates the amount of light, and the retina serves as the projection surface. Similarly, the Camera Obscura allows light through a pinhole into a lightproof box, where it forms an image on the back wall or on photosensitive paper. In both cases, the image appears inverted and mirrored – a phenomenon that puzzled scientists for centuries until the Camera Obscura made the mechanics visible.

The Camera Obscura

The differences, however, are significant. Unlike the simple pinhole of the Camera Obscura, the eye has a lens that continuously focuses and adjusts, providing sharp and detailed vision. Moreover, the eye does not merely project light; it translates it into electrical signals, which the brain interprets into coherent images. The Camera Obscura, by contrast, shows a direct, unprocessed projection – an optical truth untouched by interpretation.

This comparison was revolutionary in the history of science. The Camera Obscura demonstrated that the image on the retina is indeed inverted, and that it is the brain’s task to correct and interpret it. It bridged the gap between optics and biology, offering a tangible model for understanding how we see.

Today, the Camera Obscura is more than a scientific analogy. In art projects like The 7th Day, the same principle is used to capture long exposures that reveal traces of time and light invisible to the human eye. While our eyes capture the present moment, the Camera Obscura preserves the continuum of time, offering us a vision that goes beyond natural perception.