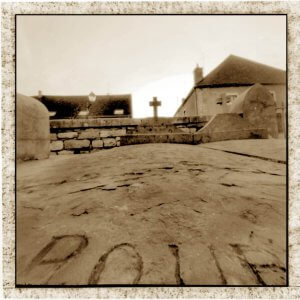

Following the footsteps of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce – * 7. March 1765 in Chalon-sur-Saône, Frankreich; † 5. Juli 1833 in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce Niépce, who had one sister and two brothers, was an officer in the French army from 1789 to 1811. He managed the Nice district from 1795 to 1801, then dedicated himself to mechanical and chemical works with his brother Claude Niépce. From 1815 he focused on the lithography. From 1816 onwards, Niépce began to produce images with a camera obscura.

The First Photograph in the World

In May 1816, Niépce attached sheets of paper coated with silver salts (silver chloride) to the back of a pinhole camera. In this way, he created the first photograph of the world: a view from the window of his study. The result was a small, inverted negative image of the outside world. However, the picture was not permanent – once exposed to light again, the silver salts continued to darken until the image vanished. Niépce called this process “Retina.” This very technique is also the basis for the long exposure photography we use in our The 7th Day project.

From Guaiacum Resin to Bitumen of Judea

Disappointed by the fleeting nature of these first results, Niépce turned in 1817 to guaiacum resin. This yellow resin turned greenish when exposed to daylight and was difficult to dissolve in alcohol, which suggested the possibility of producing more durable images. However, guaiacum only reacted to UV light, which was largely filtered out by the glass lenses of the camera obscura. As a result, no lasting images could be produced inside the camera – only direct sunlight contact prints were possible.

Niépce then experimented with bitumen of Judea, a dark, tar-like mineral mined near his home in Seyssel. When finely ground and dissolved in lavender oil, it could be spread thinly on copper plates, tin, or glass and then hardened on a hot plate. Once exposed in the camera obscura for several hours or even days, the illuminated parts of the coating hardened, while the less exposed areas could be washed away with a mixture of lavender oil and petroleum. Niépce described this process in detail in his Notice sur l’Héliographie (1829).

Niépce and Daguerre – Collaboration and Competition

In the following years, Niépce collaborated with Parisian artist Louis Daguerre, who was also experimenting with optical methods. Together they searched for ways to make images permanent. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued their experiments and developed the process that would later bear his name: the daguerreotype.

While Niépce’s heliography laid the foundation for modern photography, it was the daguerreotype that gained international recognition. It was easier to handle, required shorter exposure times, and could be marketed more successfully. Niépce himself never lived to see great success – his heliographic technique gradually faded into obscurity, even though his first photograph in history remains a milestone.